Exploring Exoplanets: A Peek Beyond Our Solar System

The vast cosmos, often described as infinite, holds a breathtaking array of planets. From the darkest planet: TrES-2b, a world that absorbs nearly all light like a mini black hole, to the pookiest planet: GJ 504b, a magenta giant floating in the inky blackness of space, the universe is a collection of unique celestial oddities. Almost every astronomy enthusiast has their favourite planet, but how do we find these distant worlds and why do they have such peculiar names?

Finding exoplanets is no easy feat, but ingenious scientists have developed several clever methods to uncover these hidden gems. The most commonly used methods include:

Transit Photometry

A method that relies on observing the slight dimming of a star's light as an exoplanet passes in front of it. Imagine a tiny insect briefly crossing a distant streetlight; the light dims ever so slightly. This is essentially what we're looking for. The Kepler Space Telescope used this technique to discover thousands of exoplanets, including TrES-1b and Kepler-452b.

Radial Velocity

To understand this method, imagine swinging a ball on a string. Your hand is like the star, and the ball is like the planet. As you swing the ball, your hand moves in a small circle too or “wobbles” about a point, because you're holding the string. Even though the ball is doing most of the moving, your hand is affected by it. The radial velocity method is akin to observing the motion of your hand to determine if there's a ball on the string.

Gravitational Microlensing

Imagine a traffic jam on a single-lane road. For a brief period, cars bunch up, making that spot appear more crowded. Similarly, when a star passes directly in front of a more distant star, its gravity acts like a lens, temporarily magnifying the background star's light. If a planet orbits the foreground star, it adds a tiny, extra flash of light to this magnification.

One might wonder: why not just take direct photos of these exoplanets? While direct imaging is possible, it is quite challenging. Exoplanets are incredibly faint compared to their host stars, making them difficult to find. It's like trying to spot a firefly next to a powerful floodlight. These indirect methods have proven to be much more effective for now.

What's with the Weird Names?

When an exoplanet is first discovered, it receives a designation based on the survey or telescope that found it. For example, the first planet found orbiting the star 51 Pegasi was designated 51 Pegasi b. The lowercase "b" is to show that it is the first planet discovered in that system. Succeeding planets are given the letters c, d, e, and so on. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) is responsible for standardising the naming of astronomical objects, including exoplanets.

While there aren't strict rules for naming (besides the initial designation), the IAU encourages short, pronounceable, non-commercial, and non-offensive names, making them accessible to a global audience.

The Future of Exoplanet Discovery

The study of exoplanets is a rapidly evolving field. Thanks to advancements in telescope technology and data analysis techniques, new discoveries are constantly being made. Launched in 2021, the James Webb Space Telescope is set to revolutionise our understanding of exoplanet atmospheres and their potential for habitability.

By studying exoplanets, we can gain a better understanding of the formation and evolution of planetary systems, as well as the potential for life beyond Earth. The search for exoplanets is a journey of exploration and discovery, one that promises to reveal even more wonders of the universe.

Similar Post You May Like

-

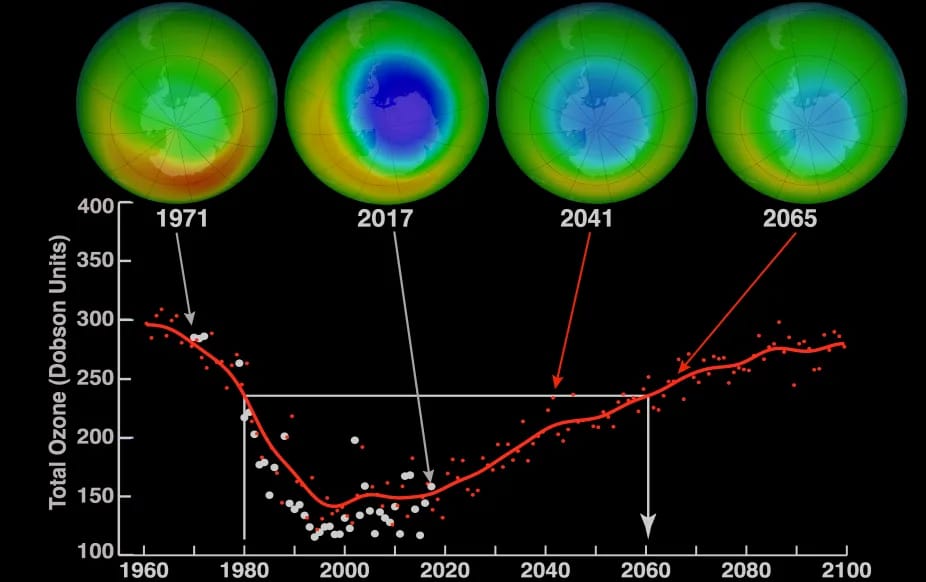

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.