Meet Your Microbes: The Tiny Tenants Living Inside You

Human microbiome is the term used to describe the distinct microbial communities that inhabit different host environments on the body’s skin and mucosal surfaces. Historically, microbiologists referred to microbial populations routinely found on and in the body as normal flora. The term microbiome also encompasses all of the genetic material associated with these normal constituents. The genetic capabilities of any given normal flora organism can have profound and important impacts on the interactions that the microbe has with the host. The establishment of the human microbiome is initiated immediately after birth and is a necessary and normal part of human development. Until relatively recently, our understanding of the organisms that compose the human microbiome relied on cultivation to isolate organisms in pure culture. This approach is limited in its usefulness for several reasons. First, the vast majority of microbes associated with humans cannot be cultivated ex vivo. Second, the ability to culture a microbe does not yield any information on the relative abundance of that organism in the niche under investigation. Finally, growing an organization out of its environment in pure culture gives little, if any, information on the complexity and interdependence of the microbial communities in that niche.

The development of sophisticated molecular techniques over the past decade has revealed enormous numbers of bacteria, yeasts, and protozoa that are associated with the human microbiome, many of which were previously unknown. Current estimates suggest that there is an approximately equal number of prokaryotic cells on and in the human body as there are human cells, most of which are gut associated. This remarkable statistic is even more notable considering that the average adult gut is home to approximately 1000 bacterial species, each of which contains approximately 2000 genes, cataloging a total of 2,000,000 gut associated microbial genes. This is 100 times more than the approximately 20,000 genes encoded in the entire human genome. Variation in the abundance and complexity of the microbiome constituents is observed within an individual over time and certainly between individuals. However, longitudinal characterization of the human gut microbiome has shown that within the first few years of our life, our microbial communities mature and become relatively stable and unique to each individual unless perturbed, such as by antibiotic treatment. Once established, members of the microbiome are considered permanent residents of associated body sites, such as the skin, oropharynx, colon, and vagina. These microbes are often referred to as commensals, which are organisms that derive benefit from another host but do not damage the host.

Members of microbiota vary in both abundance and type from one body site to another. Internal organs usually are sterile, although the central nervous system, blood, lower bronchi and alveoli, liver, spleen, kidneys, and bladder experience occasional transient microbial intrusions, often introduced after modest trauma or abrasions on the skin. We make a distinction between established members of the microbiome and something called the carrier state. The term carrier implies that an individual has become colonized with a potential pathogen and therefore can be a source of infection of others. It is most frequently used in reference to a person with an asymptomatic infection or to someone who has recovered from a disease but continues to carry the organism and can serve as a reservoir of infection for others. We have known for some time that individual members of the normal flora can cause disease when they gain access to other body sites. Examples of this include Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis, both of which are normal flora organisms of the intestinal tract, which cause urinary tract infections and peritonitis, respectively. However, there is mounting evidence that the dynamic nature of the microbiome composition plays important roles both in the maintenance of health and in the etiology of disease. Dysbioses of the microbiome, which refer to any change in the composition of resident commensal communities relative to the community found in healthy individuals, are associated with an expanding list of chronic diseases including obesity, inflammatory bowel diseases, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, colon cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, major depression, Parkinsons disease, and autism spectrum disorder. By nurturing our microbiome, we can unlock a healthier, happier us – and a brighter future for generations to come.

Similar Post You May Like

-

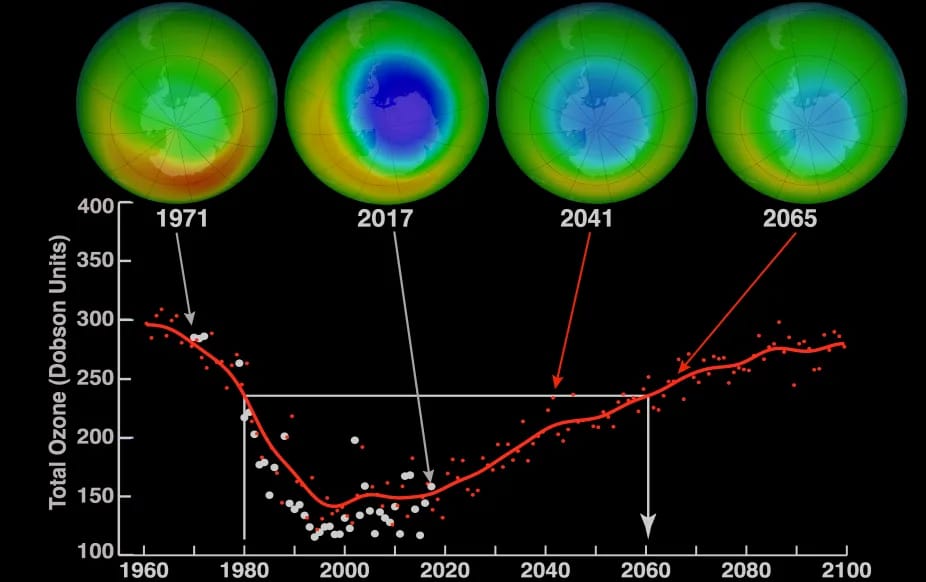

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.