“I miss…”: Nostalgia, the Unifier

“Back in the good ol’ days” is possibly the best example of the quintessential cliché proverb – overused, hyperbolized, and turned into a Macklemore song. And like the song, the proverb conveys one fundamental idea: a longing for a time past, perceived now as “good” (whether or not it was truly as good as remembered or entirely idealized): a feeling we are familiar with as nostalgia.

Etymologically, “nostalgia” is a combination of the Greek nostos and algos, meaning “returning home” and “pain” respectively. The term was used as early as 1688 by physician Johannes Hofer to describe homesickness, particularly a branch displayed in the symptoms of Swiss mercenaries serving under European monarchs (Wildschut et al., 2008). In modern-day psychological terms, “nostalgia” refers to a complex emotion marked by “past-oriented cognition and a mixed affective signature”, meaning it is regarded as an overwhelmingly positive experience, but not always (University of Southampton, 2012). However, although the experience of nostalgia is commonplace, its understanding is less so.

When it was first coined, Hofer considered “nostalgia” a disease, characterized particularly by obsessive reminiscing, weeping, anxiety, inability to sleep, and palpitations. Parisians in the 1800s were said to have died from this “cerebral disease” (Arnold, 2024). It was in the 1900s that nostalgia came to be considered a psychological disorder, progressing in the 21st century to its present-day definition. According to modern research, nostalgia is triggered by sensory inputs – the smell of your childhood home, the music of your favorite ice cream van, conversations about the past or reliving similar experiences in the present (Oba et al., 2015). These external stimuli affect the regions of the brain responsible for self-reflection, autobiographical memory, emotional regulation and reward processing functions, according to one neural model based on neuroimaging evidence (Yang et al., 2022). Typically, the memories we land upon in such nostalgic periods belong to something called the “reminiscence bump” – a period of memories between the ages of 15 and 30, when a large part of our identities come into being (Munawar et al., 2018).

But as is the case with all human emotions and struggles, there must be a reason for this emotion beyond simple wistfulness. According to Krystine Batcho, PhD, in its multitude of functions, a standout role that nostalgia plays in the human psyche is unification; of the self across time, and of the self with others. In her words, a fundamental purpose of nostalgia is to consolidate the identity of an individual, allowing for a forward-facing idea of who an individual would like to become based on ideals and ideas from their past. Moreover, nostalgia is regarded as a prosocial emotion: it serves to unite different individuals together based on collective memories and shared experiences, enhancing relationships and connectedness by emphasizing the positive nature of the shared memories (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Beyond its “unifier” role explained by Dr Batcho, nostalgia acts as a “comfort blanket” of sorts, or more accurately, as an emotional regulation strategy. It is a method of weathering the storm of change, whether it be positive or negative, and more importantly, allows space for dealing with negative emotions. Researchers at the University of Southampton found that nostalgia is more often found in individuals experiencing loneliness or pain as opposed to “happy” individuals, displaying a link between negative emotions and nostalgia and inferring that the purpose of nostalgia is to help deal with such emotions. In order to test this hypothesis, they conducted an experiment that involved participants recounting either a nostalgic or ordinary experience from their daily lives, then completing a survey. The experiment found that nostalgic participants displayed higher levels of self-esteem and improved moods, and as suggested by Dr Batcho, also displayed higher levels of prosocial attitudes.

These studies found that nostalgia may actually protect individuals from negative emotions, even in the face of morbid topics like death. An experiment was conducted with participants asked to write about their own deaths, with some being asked to recount a nostalgic experience following this activity. Afterwards, they participated in a word completion task; the results found that the non-nostalgic group predominantly answered with death-related words, whilst the nostalgic group was able to focus on more neutral or positive answers. On the whole, the experiment revealed that nostalgia could act as a source of comfort in the face of morbidity, both by preventing distress and as an alleviator of negativity, allowing individuals to connect meaning to their lives (SciShow Psych, 2018).

In light of the above research, it appears that nostalgia and optimism are intrinsically linked. However, it is necessary to remember that nostalgia is a complex emotion – alongside its many benefits, it may also carry some harm. Among its most poignant and pervasive side effects is its ability to alter memories, often framing them in a significantly more positive light than they were in reality (SciShow Psych, 2018). Additionally, nostalgia, or more accurately, excessive indulgence in nostalgic memories, can become a hindrance to personal growth and evolution. This is because of the unhealthy attachment that forms between the individual and the past, which prevents them from accepting, and even more so, exploring the present. In turn, this forces them to paint the present in a comparatively negative light. Research published in the European Journal of Social Psychology also suggests a positive correlation between nostalgia and anxiety. It found that participants with an inclination towards worrying experienced a heightened sense of anxiety and depression when exposed to nostalgic stimuli (UF Health, 2025). At an interpersonal level, excessive nostalgia for a historical past where the persistent evils of the time are either ignored or glorified may even present dangers for the upkeep of relationships (Stoycheva, 2020).

At the end of the day, the dangers of nostalgia only become a peril when we disturb the equilibrium of reminiscing on the past and existing in the present, and its overwhelmingly positive impacts on the human psyche present it as an emotion that can potentiate an elevated and enhanced form of life. And although one day we will “miss the magic of the good old days”, as Macklemore said, perhaps there is a different magic still left to us in their wake – nostalgia.

References

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Speaking of Psychology: Does nostalgia have a psychological purpose?

- Arnold, A. (2024, April 28). That yearning feeling: why we need nostalgia. The Guardian.

- Munawar, K., Kuhn, S. K., & Haq, S. (2018). Understanding the reminiscence bump: A systematic review. PubMed Central.

- Oba, K., Noriuchi, M., Atomi, T., Moriguchi, Y., & Kikushi, Y. (2015). Memory and reward systems coproduce ‘nostalgic’ experiences in the brain. National Library of Medicine.

- SciShow Psych. (2018). The Unexpected Benefits (and Risks) of Nostalgia. YouTube.

- Stoycheva, V. (2020). The Dark Side of Nostalgia. Psychology Today.

- UF Health. (2025, January 8). The Psychology of Nostalgia. University of Florida.

- University of Southampton. (2012). What Nostalgia Is and What It Does.

- Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Routledge, C. (2008). Nostalgia - from cowbells to the meaning of life. British Psychological Society.

- Yang, Z., Wildschut, T., Izuma, K., Gu, R., Luo, Y. L.L., Cai, H., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Patterns of brain activity associated with nostalgia.

Similar Post You May Like

-

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

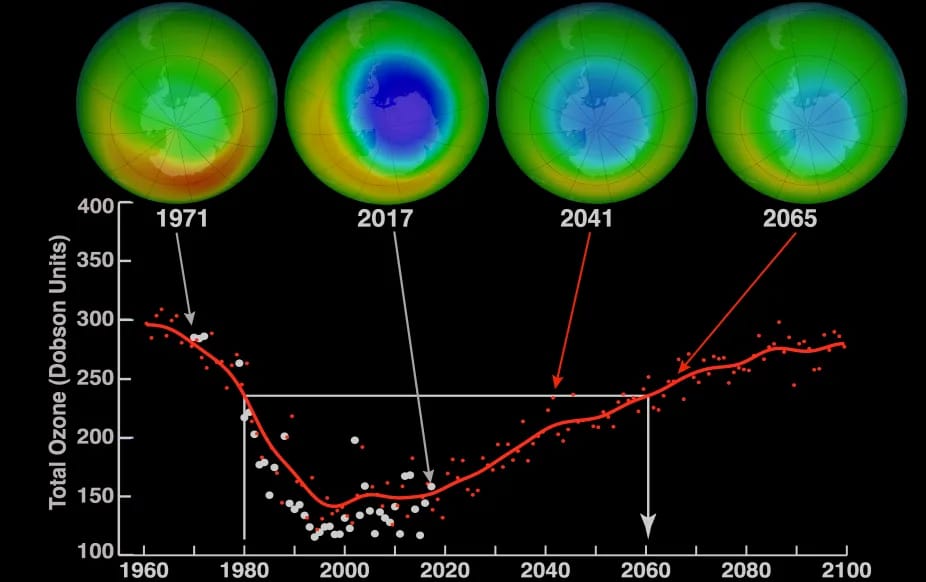

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.