Brain Surgery but make it Retro: Lobotomies Explored

Who needs their frontal lobe anyway, right? In the not-so-distant past, doctors believed that the key to curing mental illness was not just medication or therapy, but a simple, yet horrifying procedure. Picture this: instead of healing minds, doctors decided to sever connections in the brain, ALL IN THE NAME OF SCIENCE? Here you have it! Lobotomy — a surgical intervention that sliced into the brain with an ice pick, in the hope of erasing symptoms of insanity. This chilling practice was once thought to be a miracle cure, but what happened when the human mind became nothing more than a puzzle to be rearranged? The world of lobotomy is one where science, ethics, and madness collide in a strange, eerie dance.

Lobotomies were majorly used to treat psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, depression and anxiety. It was thought that severing the connections in the brain's frontal lobe would relieve these conditions and calm patients who were regarded as difficult or unmanageable. At the height of its use, lobotomy was considered a revolutionary cure. Medical professionals even called it a blessing for people suffering from mental health issues.

In the late 1800s, Gottlieb Burkhardt, a Swiss doctor who supervised an insane asylum, had operated on patients who heard strange voices or showed other signs of mental illness. Burkhardt’s goal was not to make the patients sane again, but to make them calmer. He removed parts of the brain in six patients. One of the patients died a few days after the surgery and the second one committed suicide later (however there is no evidence of the suicide being connected to the surgery). On the other hand, some of the patients became easier to handle. Burkhardt was influenced by German scientist Friedrich Goltz, who had performed similar experiments on dogs. Goltz removed parts of the dogs' brains and observed changes in their behavior. Burkhardt’s work sparked interest, but for many years there were few attempts at similar surgeries on humans.

In 1935, American scientists Carlyle F. Jacobsen and John Fulton conducted an experiment on chimpanzees involving frontal lobe ablation (ablation means removal or destruction of any body part or tissue). One of the chimpanzees, previously agitated by mistakes during a memory task, showed no such reaction after the operation. However, the other chimpanzee, which had been calm before the procedure, became agitated afterward.

By 1936, Portuguese neurologists António Egas Moniz and Almeida Lima introduced the prefrontal leukotomy. This procedure involved severing connections in the brain. The procedure was later modified in 1935 by American neurologists Walter J. Freeman II and James W. Watts. Freeman became a key figure in promoting lobotomy and the media helped him create a public frenzy over its supposed success.

This led to many people asking for the procedure. In 1945, Freeman changed the method again and created a “transorbital lobotomy.” In this version, a sharp tool was inserted through the eye socket to reach the frontal lobe and cut important connections in the brain. This new procedure became widely known and used, despite its serious risks and damaging effects.

This operation was often performed with little regard for patient consent or comfort and anesthesia was rarely used. The act itself was intrusive and brutal. Without a doubt, it created immense trauma to those who underwent it.

While some patients showed initial signs of calm, the long-term effects were far more disturbing. Many individuals became emotionally numb, lost their ability to think critically and to engage meaningfully with their surroundings. Their personalities, once vibrant and unique, were often wiped away. In many cases patients became passive or even unrecognizable to those who knew them. What was initially seen as relief soon revealed itself to be a devastating alteration of one's identity.

A 2018 study also states that most lobotomized people were women. Many of these women were diagnosed with conditions like anxiety, depression, or even "hysteria" — a term often used to dismiss women’s emotional struggles in the past. Women who defied traditional roles or exhibited behaviors considered "unmanageable" were more likely to be subjected to lobotomies because the procedure was seen as a way to "calm" or "control" them. Out of Freeman’s first twenty psychosurgery patients, seventeen were women.

Lobotomies were not a standard treatment for physical conditions like brain tumor or ulcerative colitis and did not result in long-term improvements for patients suffering from such ailments.

The procedure gained more attention and soon the negative outcomes of lobotomy became apparent. Some doctors began exploring other controversial and dangerous methods for treating mental illness. One such method involved injecting radioactive materials, such as iridium, through the eye socket!

Eventually, lobotomy was abandoned, but its legacy serves as a haunting reminder of the dangers that arise when science is practiced without full understanding or consideration of its human cost.

Similar Post You May Like

-

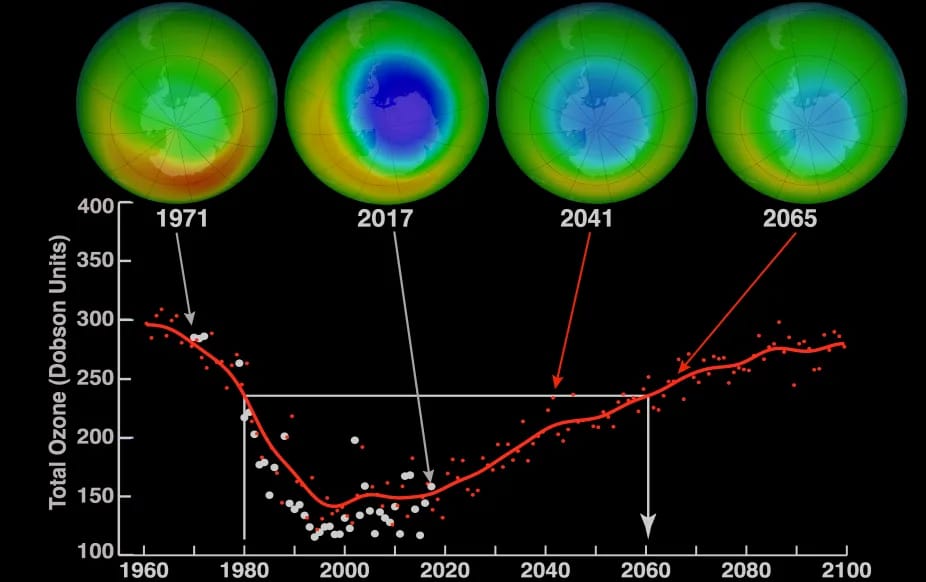

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.