You are what you eat: how your gut microbiome is affecting your brain

Meet Your Second Brain

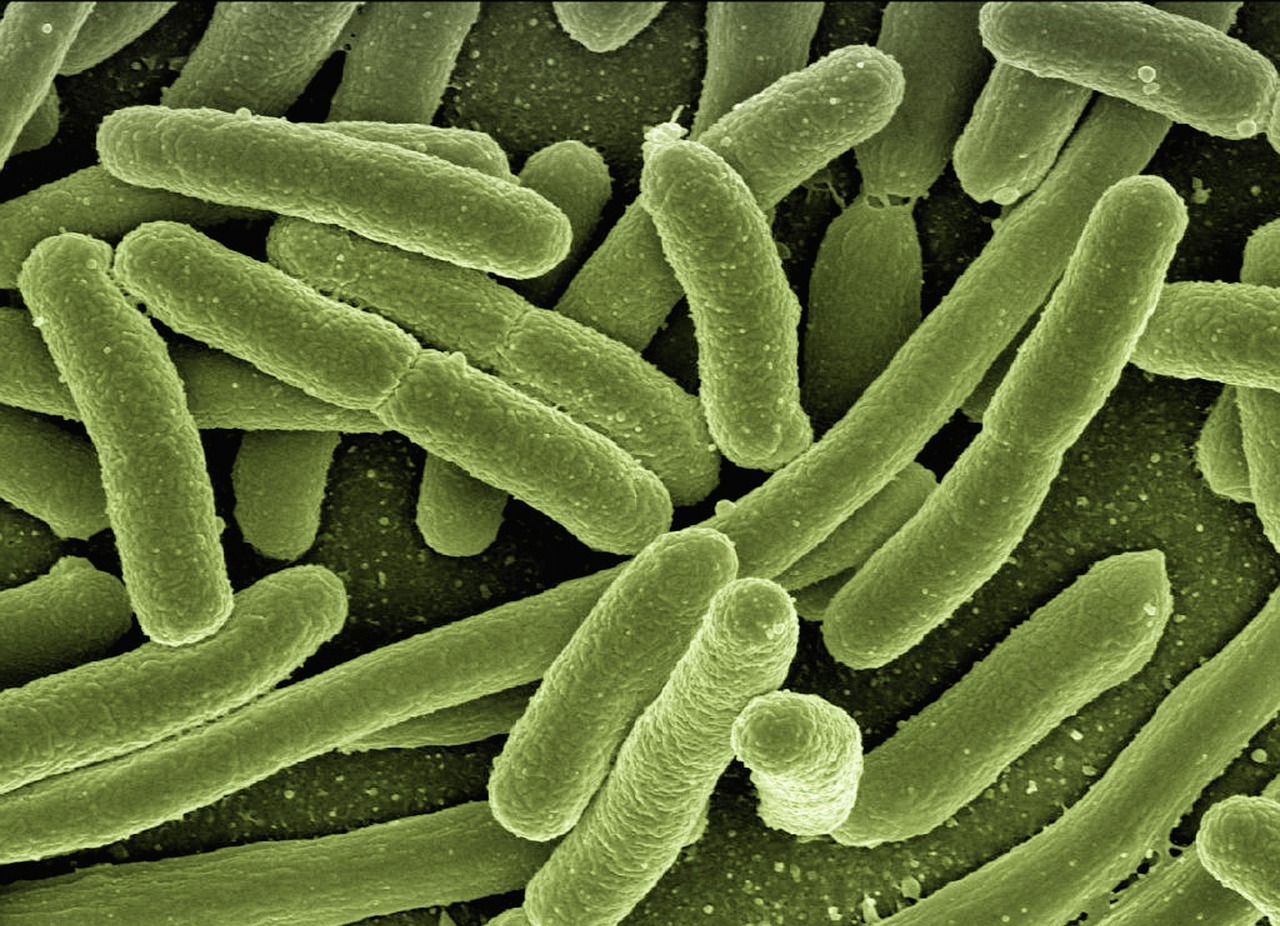

If you've ever experienced the jitters before going on stage or felt butterflies in your stomach before an interview, you're likely getting signals from your second brain, the gut. This marvel of design and communication is home to viruses, fungi, and microorganisms, which make up the microbiome unique to each individual, influenced by environment, genetics, and diet.

The human body is not only designed to accept the invasion of these microorganisms but to welcome it. They are omnipresent just like on your screen right now. It is important to understand that our gut does far more than just break down the food we eat. The tiny yet innumerable colonies of specific microorganisms in our gut have an irrefutable role in our health and well-being.

This article explores the influence of gut health on cognition and behavior and delves into the intricate wiring of chemical communication that allows our digestive system to profoundly influence our mind.

The Gut-Brain Axis — A Two-Way Communication Street

We are aware of how the brain influences activity in our gut, like digestion and gastrointestinal motility, but the other way around is also possible. The gut and its microbiome affect the functionality of our brain. This is due to the bidirectional signaling between the brain, gut, and the gut microbiota, also known as the gut-brain axis.

On a lighter note, we may also say that the two “talk” to each other. The gut-brain axis (GBA) links emotional and cognitive centers of the brain with peripheral intestinal functions.

The Vagus Nerve

Numerous psychiatric and neurological conditions have been linked to disturbances in gut microbiota. It all starts with the vagus nerve—the longest nerve in the body—being particularly active in the gut. It is the most direct route linking the gut and the brain.

Activity in this nerve has been linked to behaviors like feeding and socializing and to anxiety and depression. The vagus nerve can be activated by gut microbiota, transmitting information from the gastrointestinal tract to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), which further relays information to the central autonomic network.

Studies show that individuals experiencing mental health disorders often exhibit declining levels of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, two essential bacteria in a healthy gut ecosystem.

The Gut’s Role in Stress and Anxiety

The gut microbiota also affects our body's response to stress through the HPA axis, which regulates hormones such as cortisol. A 2020 study on mice showed that probiotic supplementation reduced stress-induced corticosterone levels and anxiety-like behavior.

Additionally, multiple clinical trials concluded that probiotics containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium significantly reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Emerging research suggests that poor gut health may also be linked to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease have been found to exhibit lower microbial diversity, including reduced levels of anti-inflammatory bacteria like Eubacterium rectale.

How the Gut Makes “Feel-Good” Chemicals

This complex communication system influences mood and motivation by triggering gut cells to produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine. Nearly 90 percent of serotonin in the human body is produced in the gut.

Serotonin promotes feelings of happiness and emotional stability, while dopamine increases motivation and reward processing. Gut microbiota also influences immune signaling and inflammation, both of which strongly impact the nervous system.

Approximately 70 percent of the human immune system resides in the gut, where a healthy microbiome trains immune cells and reduces harmful inflammation.

From Food to Mood: The Metabolic Process

Improving gut health is a promising approach to improving mental well-being. A healthy gut microbiome can enhance energy levels, mental clarity, emotional balance, and recovery time.

Gut bacteria metabolize biomolecules such as fats, lipids, and proteins. Tryptophan, found in foods like chicken, eggs, and nuts, is converted into serotonin and later into melatonin, which regulates sleep.

Tyrosine, present in almonds and lentils, is converted into dopamine, a neurotransmitter that enhances motivation and daily productivity.

Food as Medicine

Hippocrates famously stated, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” highlighting the therapeutic power of nutrition. Eating habits directly shape the diversity and resilience of the gut microbiome.

Research indicates that improving diet quality alone can reduce symptoms of major depression. A fiber-rich diet including fruits, vegetables, and whole grains supports beneficial bacteria, while reducing added sugars helps limit inflammation.

The food we consume not only builds our bodies but also shapes the microbial ecosystem that communicates with our brain. By nurturing our gut, we invest directly in mental resilience and emotional health. The future of mental health may lie as much in diet and lifestyle as in medication.

References

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2023). The Gut-Brain Connection. National Institutes of Health.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2022). Vagus Nerve Stimulation May Be Helpful for Post-Stroke Movement.

- Wallace, C. J. K., & Milev, R. (2017). The effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans. Annals of General Psychiatry, 16(1), 14.

- Vogt, N. M., et al. (2017). Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 13537.

- Jacka, F. N., et al. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (SMILES trial). BMC Medicine, 15(1), 23.

Similar Post You May Like

-

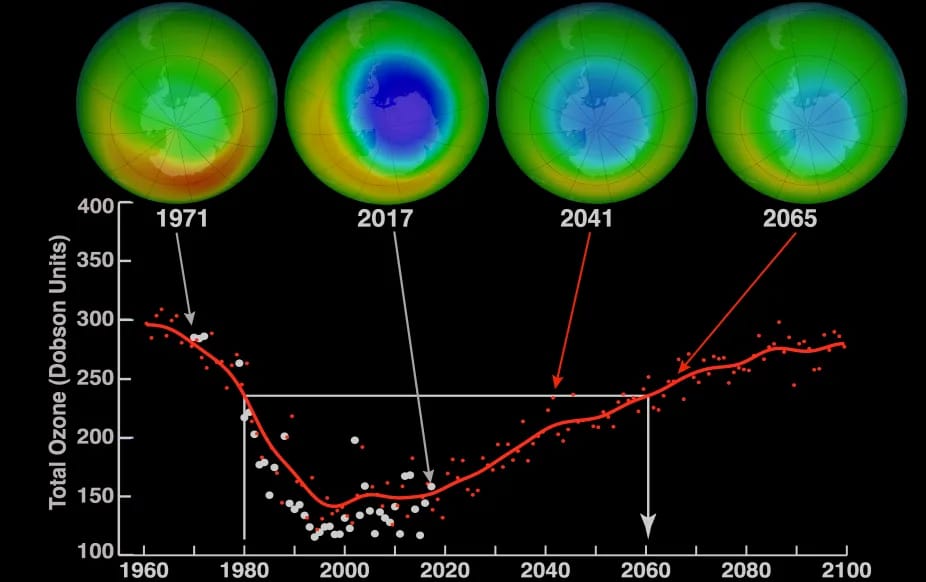

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.