Ripples in the Fabric of the Universe: An Inquiry into Gravitational Waves

Among the many consequences of Einstein’s theories of relativity is the complete overhaul of our conception of space and time; no longer two distinct entities, these inseparable concepts combined to form the very fabric of our reality, forming a four-dimensional spacetime (first called so by Hermann Minkowski, a former professor of Einstein attempting to formulate a geometrical interpretation of his former student’s ideas). Under this new model, all of reality existed under a more tangible conception of space and time, one that was both shaped by the things within it while influencing them as well.

To make this abstract idea more intuitive, one of the most common analogies to help us understand this version of spacetime—so different from the unaffected abstraction it once was—is that of an elastic fabric. The fabric bends when weight is put on it, such as that of a planet or a star, resulting in the curvature of space time around such heavy objects.Furthermore, the fabric extends into four dimensions, making it harder to visualise yet explaining how its bends and curves affect space in all three directions as well as affecting time equally.

As a consequence of this fabric-esque reality, spacetime can warp in unusual ways; it acts as a medium to be travelled through rather than a mere emptiness in space. For instance, when large objects move through it, they create ripples similar to those produced by a body moving through a body of water. These ripples are known as gravitational waves. First proposed in 1893 by Oliver Heaviside and later confirmed by Einstein as an inevitable consequence of his theory of general relativity, these waves provide us with a conception of gravity vastly different than that of Newton’s. They show that gravity behaves as distortions in spacetime and can radiate outward in a manner akin to electromagnetic radiation. Furthermore, these ripples can alter the distances of objects they pass through, stretching and squeezing the spaces between them.

So, do we cause ripples in space-time? In principle, yes, but the waves generated by us are far too small to be detected. The major sources of detectable gravitational waves in the universe come from rapidly moving, heavy celestial objects, especially ones in spiral-like motion. These include binary black-hole mergers (as a result of two black holes colliding), neutron star collisions and supernovae (when a star collapses in a violent explosion). Gravitational waves from the Big Bang are also thought to still be propagating throughout the universe to this day, albeit at a greatly diminished frequency.

Though they were proposed over a century ago, gravitational waves weren’t observed until 2015 by LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory). That’s because the waves that do reach us are quite faint and it wasn’t until recently that technology could detect them. So how did LIGO do it? The answer lies in exploiting a gravitational wave’s property of subtly altering the distances between objects it passes through.

LIGO’s detectors consist of a giant L-shaped structure with each arm about four kilometres long, intersecting at right-angles. Light beams are subsequently sent down each of these arms and are reflected at the ends of the arms by mirrors. Once these beams return to the intersection, they meet and perfectly cancel each other out in a phenomenon known as destructive interference. All of this occurs under normal conditions.

However, when a gravitational wave passes through the structure, it alters the distances of the arms by stretching one and squeezing the other. Though these fluctuations in distance are almost imperceptibly small, they are just large enough to alter the journey of the light rays so that they no longer destructively interfere when reflected back from the edge of the arms. This is because one beam travels a slightly longer path and the other a slightly shorter one, they no longer meet in sync, and instead combine in varying degrees. Detectors at the intersection pick up on this change and register the gravitational wave (after any anomalies and errors are ruled out).

The first successful detection by LIGO took place on September 14, 2015^1, when gravitational waves from a black hole merger around 1.3 billion light-years away were detected. Consequently, the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to physicists Rainer Weiss, Kip S. Thorne and Barry C. Barish for their contribution to LIGO and the detection of the long sought after phenomenon^2.Today, in addition to the two LIGO detectors in the USA, other observatories such as Virgo in Italy, GEO600 in Germany and KAGRA in Japan also work to detect gravitational waves and collaborate on locating their origins in space and time.

With advancements in gravitational-wave detecton technology, many new possibilities at the frontiers of science have opened up. Beyond confirming Einstein’s theory of relativity and predictions made more than a century ago , they mark a significant change in interstellar observations. Scientists were previously reliant on electromagnetic radiation to detect far off stellar objects, but the new form of radiation has allowed us to observe distant phenomena otherwise incredibly difficult without being seen directly and unobstructed. Since gravitational waves are unaffected by interstellar dust or gasses, they can give us a clearer picture than electromagnetic waves which are obscured by such obstructions.

Furthermore, future developments, such as the LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) mission (the first space-based observatory to study gravitational waves), which aim to detect lower frequency gravitational waves so that we can detect much further and older phenomena, such as the ripples in spacetime caused by the Big Bang and by potential supermassive black holes, allowing us to study the properties of black holes and neutron stars, probe the early universe and test theories of gravity. Moreover, they can give us information on the great mysteries in physics such as the truth behind dark matter and what the universe was like in the beginning before light existed.

Image 1: File:Spacing time 2.jpg. (2024, July 11). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Spacing_time_2.jpg&oldid=897010182.

Image 2: File: Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Laser-Interferometer-Gravitational-wave-Observatory#/media/1/1562918/205865

1: B. P. Abbott1, R. Abbott1, T. D. Abbott2, M. R. Abernathy1, F. Acernese3,4, K. Ackley5, C. Adams6, T. Adams7, P. Addesso3 et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration), 11 February, 2016. Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger, Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 061102: https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102

2: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (2017). Nobel Prize in Physics 2017, NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2017/prize-announcement/

Similar Post You May Like

-

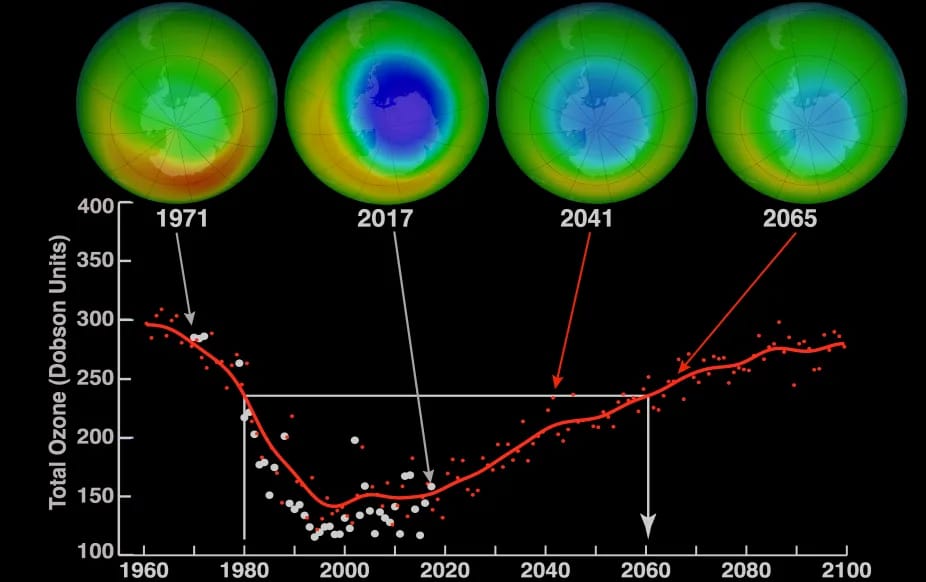

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.