So We Dance All Night…And Keep Dancing? The Deadly Dancing Mania

Faeries, to our present scientific and worldly knowledge, do not exist. However, human imagination is a limitless galaxy, and in the expanses of these fantasies and illusions, we often associate them with enchantment, trickery, and dancing. In typical folklore, faeries are mischievous beings that lead people astray — using will-o’-the-wisps, and increasingly in modern literature, by trapping their victims in eternal dance. And as fantastical as it may sound, such fiction may not be entirely mythical.

The year 1518 saw what may have been the most intriguing disease that plagued humanity in Strasbourg, France, with symptoms unlike typical maladies. “Dancing mania” (otherwise known as St. John’s dance, tarantism, and the dancing plague) would become the eventual demise of up to 400 people, according to one source. Although the incident in Strasbourg has now become the most widely acclaimed example of choreomania (i.e., the uncontrollable urge to dance), it is not the sole proprietor of the phenomenon, rearing its head for the first time in 1021 CE Germany in the town of Kolbigk in recorded history (Waller), and making numerous reappearances in the centuries to follow.

The Strasbourg incident began with Frau Troffea, as she stepped into the public eye and began her dance, sans music, sans cause. Little did her onlookers know, she would continue this dance for a week, without rest, without stopping, until her body collapsed under sheer exhaustion. But by this point, she was no solo dancer. Stages were built for the Strasbourgeois dancers to continue their manic “partying,” and these dancers, in a revel-like fashion, inexplicably maintained their festivity until they were felled, like Frau Troffea, to death; the situation of the plagued had dilapidated to the point of heart attacks and strokes.

Modern science now attempts to bring light to these inexplicable tragedies. What motivation did these towns of hundreds have to dance away their lives? The answer is found, not in fiction and fable, but in psychology. These recurrent plagues were instances of mass psychogenic illness, more often known as “mass hysteria.” Today, there is a consensus in the compromised states of the dancers’ consciousness — they moved in a trance-like state, unable to control or comprehend their actions, a consequence of unparalleled stress and distress. According to the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, mass psychogenic illness is a result of experiencing high levels of anxiety within a tightly knit group, the induced negative response jumping almost contagiously between members of the in-group (Bartholomew et al.). In 1518, the Strasbourg population had undergone severe levels of distress; in the presence of horrid harvests, skyrocketing prices, and the advent of new, inescapable diseases such as syphilis, it is apparent that these people were in a state of consistent struggle. This high-stress environment therefore provided the perfect backdrop for the collective, bizarre response we see in dancing mania, characterized by unintentional bodily movements.

While mass hysteria provides solid reasoning for this mass response, a variance of theories also present themselves to explain this odd epidemic. Primarily amongst these alternative theories is the possibility of ergot poisoning. Ergot, a hallucinogenic fungus found to grow on rye and stalks, contains chemicals structurally similar to LSD — therefore, it is unsurprising that this disease may have induced bodily spasms, and has often been held accountable for the dancing mania. However, research also states that ergot having such an impact on the dancers is unlikely: while it explains the movements and hallucinated motivations of the dancers, the fungus alone is incapable of sustaining such prolonged dance. Furthermore, with the observation of dancing mania in tropically and environmentally different regions that did not support the growth of the fungus, the theory falls short of providing a holistic understanding of the cause of the outbreaks. Other alternative explanations center around religious zeal and punishment.

Today, we may look back at these wondrous, stupendous events in disbelief and shock — perhaps not everyone feels better when they’re dancing. A case of the dancing plague has not been reported in more than three hundred years. Regardless, these plagues remain a gateway to understanding the power of collective thought and response, and an object of fascination for all, dancers and non-dancers, as a chapter of human history beyond our imagination.

Works Cited

Bartholomew, Robert E., et al. “Mass psychogenic illness and the social network: is it changing the pattern of outbreaks?” PubMed Central, 2012, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3536509/ . Accessed 21 January 2025.

Waller, John. “A forgotten plague: making sense of dancing mania.” The Lancet, 21 February 2009, https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736%2809%2960386-X/fulltext .

Similar Post You May Like

-

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

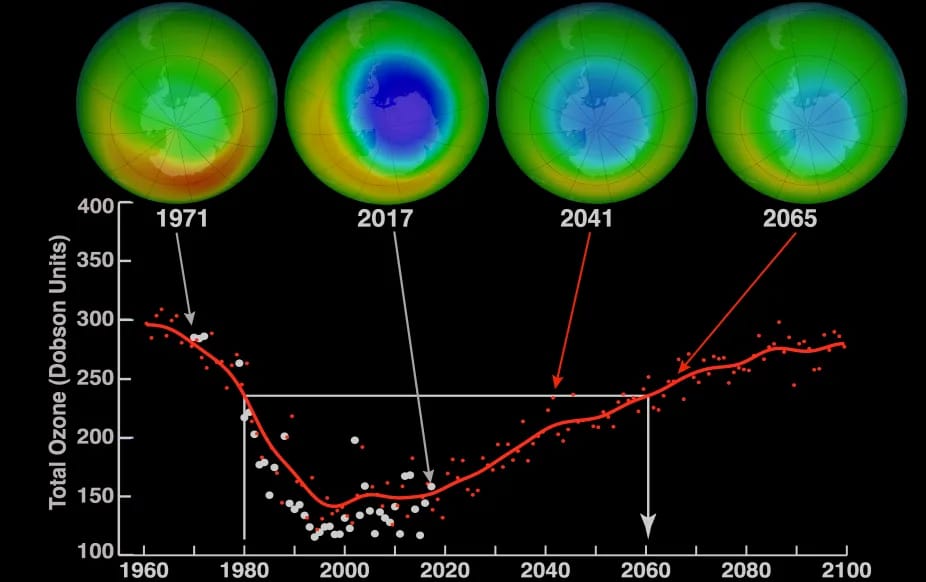

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.